Nature & Deterioration of Analog Materials: Silk Textiles

The History and Relevance of Silk

In 130 B.C.E., during the Han dynasty, China opened trade routes to the West, initiating what would become known as The Silk Road. These routes facilitated not only the exchange of goods but also religion, art, and ideas (National Geographic Society, 2024). The cultivation of silk dates back over 5,000 years to the Neolithic Yangshao culture, with the earliest surviving silk textiles originating from the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–9 C.E.), due to silk’s fragility (Saint Louis Art Museum, n.d.).

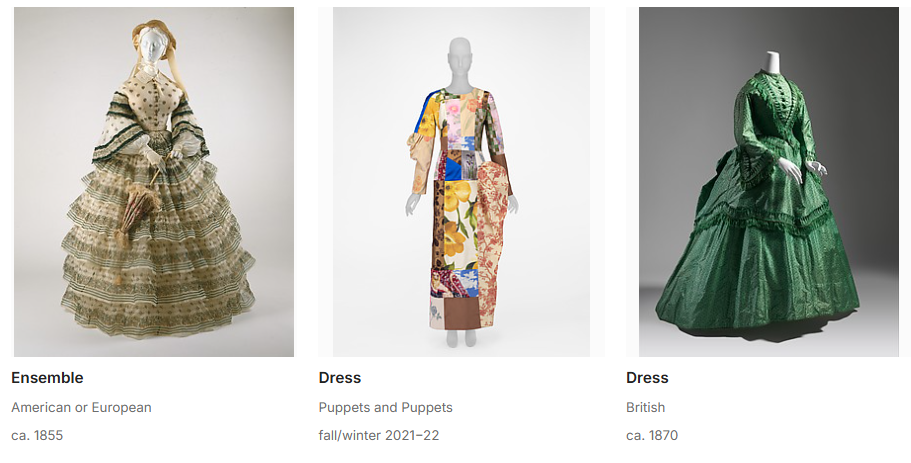

Throughout history, silk has been prized for its rarity, beauty, and versatility. It has been used in tapestries, needlework, quilts, flags, furnishings, costumes, and even medical sutures. Silk’s desirability stems from its high production costs and unique aesthetic appeal. The Met’s Costume Institute showcases silk’s enduring influence on fashion, with pieces ranging from 2000 B.C.E. to the present (The Costume Institute, n.d.). The Saint Louis Art Museum similarly holds a significant collection of Chinese silk textiles from the Ming and Qing dynasties, which include some of the best-preserved examples of this remarkable material (Saint Louis Art Museum, n.d.).

Silk’s impact extends beyond textiles, shaping technological advancements as well. By the late 18th century, cities like Lyons, France, and Spitalfields, London, were renowned for patterned silk production. As fashion evolved, looms required frequent rethreading to accommodate new patterns. To address this inefficiency, Joseph Marie Jacquard invented the Jacquard Loom in 1801, employing punched cards to control the weaving process. This breakthrough inspired computing pioneers, including Ada Lovelace, who drew parallels between the Jacquard Loom and Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, a precursor to modern computers (Sikarskie, 2016).

Production and Composition of Silk

The production of silk, known as sericulture, is as fascinating as its history. It begins with the Bombyx mori silkworm, which lays approximately 500 eggs. The larvae, fed mulberry leaves, grow 10,000 times their original size before forming cocoons. Each cocoon contains roughly half a mile of silk filament, only 0.00059 inches in diameter (Salopek, 2024). To extract this filament, the cocoons are boiled or steamed, a process that prevents the natural sericin protein from hardening the fibers. The resulting silk is then unwound and spun into thread (Egglestone, 2023).

Silk fibers are both fine and strong, offering excellent insulation and moisture absorption. Chemically, silk is composed primarily of fibroin and sericin proteins. Fibroin consists of two main components: H-fibroin (350,000 Da) and L-fibroin (25,000 Da), linked by a disulfide bridge. This unique structure contributes to silk’s durability and versatility (Vilaplana et al., 2014).

Key Challenges in Silk Preservation

A critical historic practice in silk preservation is "weighting," which emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries. To restore weight lost during degumming (removing sericin), metallic salts were added to silk. While this enhanced drape and dye uptake, it also accelerated deterioration, leaving silk brittle and fragile over time (Dancause et al., 2018).

Environmental factors like light, temperature, and humidity also contribute to silk’s degradation. A 2014 study comparing historic 17th-century silk to artificially aged silk revealed that thermo-oxidation at elevated temperatures closely mirrors the natural degradation process. Key mechanisms include oxidation, hydrolysis, and chain scission, highlighting the complexity of preserving silk textiles (Vilaplana et al., 2014).

Preservation Management Strategies

Preserving silk requires a nuanced approach to mitigate its vulnerability to environmental factors:

Light Management: Silk is highly sensitive to visible and ultraviolet (UV) light. UV light, in particular, causes significant damage in a short period. Protective measures, such as UV-filtering glass or plexiglass and LED lighting, are essential when displaying silk. When not on display, silk should be stored in complete darkness (Fahey, 2022).

Temperature and Humidity Control: High temperatures accelerate chemical reactions, while fluctuations in humidity can weaken fibers. Recommended storage conditions include stable temperatures between 65–75°F and relative humidity levels of 25–60%, depending on the season (Henry Ford Museum, 2022).

Pest Management: Insects such as moths and silverfish can damage silk. Maintaining a clean environment and conducting regular inspections are critical. Avoid pesticides when possible, as they can harm both textiles and archivists.

Handling and Storage: Due to silk’s fragility, textiles should be handled with clean, dry hands, free of creams or jewelry. Support delicate pieces with acid-free cardboard or tissue, and store them flat in drawers or boxes. Folding should be avoided or padded with acid-free tissue to prevent permanent creases (AIC, n.d.).

Conclusion

Silk is a material of extraordinary historical and cultural significance, bridging disciplines from art and fashion to technology. Its preservation requires specialized knowledge and resources, including environmental controls, pest management, and careful handling. While its fragility presents challenges, silk’s rich history makes it an invaluable asset for any archival institution. By employing best practices and consulting textile conservation experts, archivists can ensure this remarkable material endures for future generations.

Standards

ISO 15625:2014: Defects and evenness of raw silk

ISO 1833-18:2020: Mixtures of silk with wool or other animal hair

ISO 8159:1987: Morphology of fibers and yarns

ISO 16549:2021: Unevenness of textile strands

ISO 150-X08:1994: Test for colorfastness

Bibliography

American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC). (n.d.). Caring for your treasures. https://f9f7df2c79cc13143598-609f7062990e04dd7dd5b501c851683c.ssl.cf2.rackcdn.com/aichaw_22281a6ba4531c3e85ec62463e3b5b69.pdf

Dancause, R., Wagner, J., & Vouri, J. (2018). Caring for textiles and costumes. Canadian Conservation Institute. https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/preventive-conservation/guidelines-collections/textiles-costumes.html#a4

Egglestone, R. (2023, November 28). How is silk made? The ethical dilemma of its origins. Discover Magazine. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/silk-making-is-an-ancient-practice-that-presents-an-ethical-dilemma

Fahey, M. M. (2022, January 24). The care and preservation of antique textiles and costumes. Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. https://www.thehenryford.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/the-henry-ford-antique-textiles-amp-costumes-conservation.pdf?sfvrsn=2

National Geographic Society. (2024, February 9). The Silk Road. National Geographic. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/silk-road/

Saint Louis Art Museum. (n.d.). Chinese silk textiles of the Ming and Qing dynasties. https://www.slam.org/exhibitions/chinese-silk-textiles-of-the-ming-and-qing-dynasties/

Salopek, P. (2024, January 22). Cocoon of Days. National Geographic. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/cocoon-of-days/

Sikarskie, A. G. (2016). Intro. In Textile collections: Preservation, access, curation, and interpretation in the digital age (pp. 1-10). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Incorporated.

The Costume Institute. (n.d.). Search The Collection. The Met. Retrieved March 29, 2024, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search?department=8

Vilaplana, F., Nilsson, J., Sommer, D. V. P., & Karlsson, S. (2014, December 10). Analytical markers for silk degradation: Comparing historic silk and silk artificially aged in different environments. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 407, 1433-1449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-014-8361-z